Using a framework to identify and organize your processes

How do you do what you do?

Understanding, documenting, and improving how you do what you do sounds like a worthwhile endeavor, right? At its essence, this is what the organizational discipline of process management seeks to accomplish.

Whether your focus is process improvement, enabling your employees with standard work resources, building continuity into your business in preparation for the next work disruption, or satisfying compliance and regulatory goals, odds are you can benefit from process management.

But where do you start?

Begin with the end in mind

As I have recently observed, shopping for tools and technology is a tempting place to begin. But starting here would be misguided. Tools and technology are simply supporting means for executing your larger process management vision and strategy.

By way of reminder – a vision is your desired end state. This is where you answer the question: “What does good look like?” A strategy is the logical outworking of your vision. It is the high-level roadmap for how the vision will be achieved. The blog post linked above goes into more detail on these points.

So, after you have a clear process management vision and strategy in place – where do you start?

Process framework

A next logical step is to create a process framework. A process framework is a mechanism for identifying and arranging all the existing processes within an organization. It is constructed in such a way as to help show relationships and dependencies between those processes – both horizontal and vertical.

The horizontal (sequential) relationships show how value is truly created within an organization – cross-functionally. Too often organizations manage functions as silos, as if they have no interaction with upstream providers or downstream customers. This can distort the reality of value creation which inherently demands teamwork and communication across individual functions.

Regarding the vertical (parent-child) relationships between processes, a framework will decompose or disaggregate in detail from a higher-level to a lower-level. Historically, there have been various methods put forward for categorizing process information at the highest level – often called the organizational value chain or value stream.

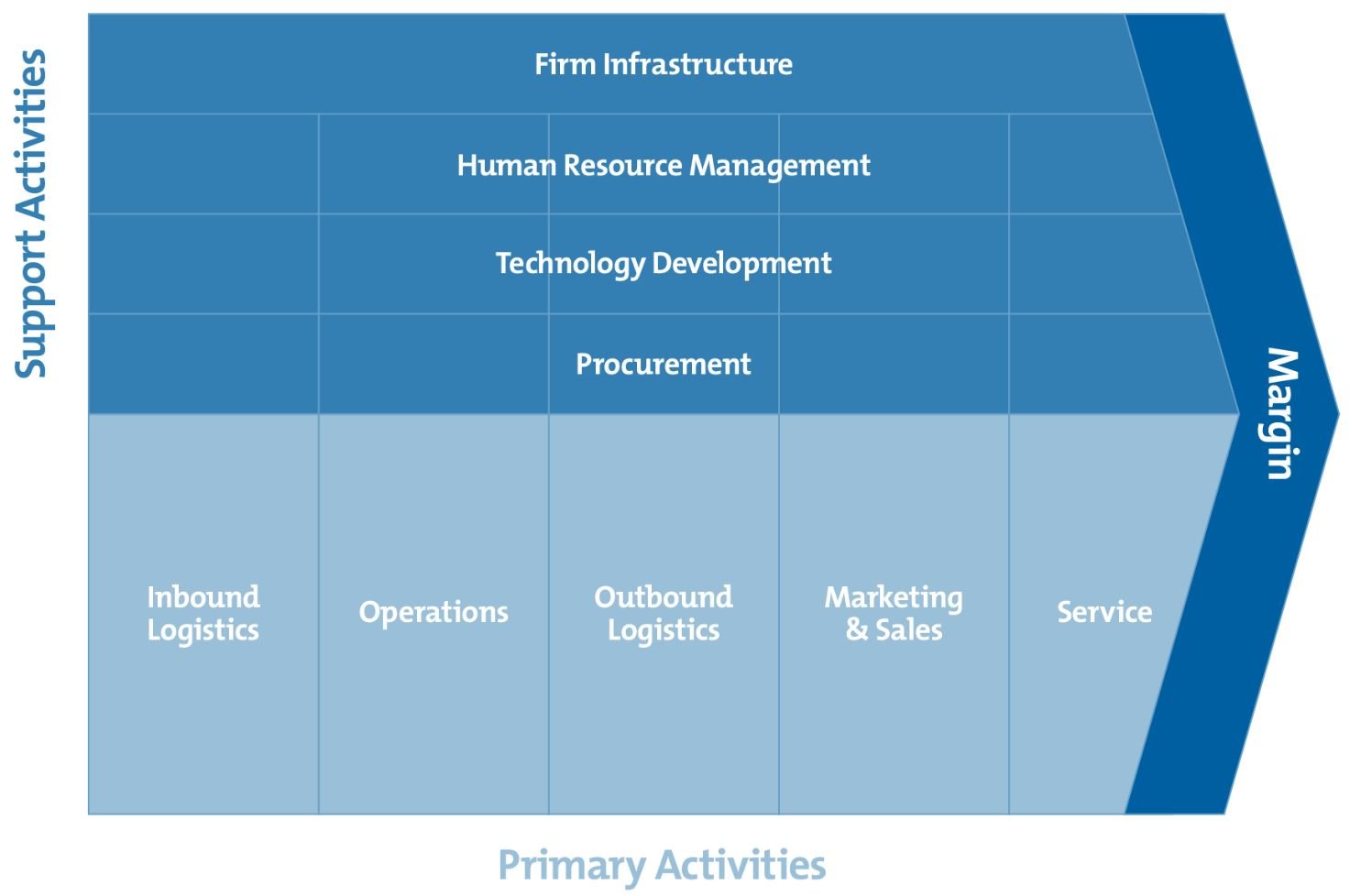

Porter’s value chain

One of the more popular models for value chain development was presented by Michael E. Porter in his book Competitive Advantage, originally published in 1985. As Porter states: “Every firm is a collection of activities that are performed to design, produce, market, deliver, and support its product. All these activities can be represented using a value chain…”[1]

Porter goes on to distinguish activities in the value chain as either primary activities or support activities: “Primary activities…are the activities involved in the physical creation of the product and its sale and transfer to the buyer as well as after-sale assistance…Support activities support the primary activities and each other by providing purchased inputs, technology, human resources, and various firmwide functions.”[2]

Others, such as Rummler and Brache identify a third distinction in those top-level processes – management processes – in addition to Porter’s primary and support processes.[3] These three categorical distinctions between high-level processes are commonly used by subject matter experts three decades later.

For example, Dumas et al. in the valuable book, Fundamentals of Business Process Management, identify three classifications of high-level process distinction – 1) core processes, 2) support processes, and 3) management processes.[4]

The APQC, likewise, in their Process Classification Framework, recognize three classifications, although they combine management and support processes under the same banner.[5]

At this point, it might be helpful to define each of the three classifications of high-level processes:

Primary processes - directly produce the value that the customer is willing to pay for. They achieve the organizational strategy and define how you do what you do.

Support processes - empower the primary processes to work as they should by providing the needed resources (human resources, IT hardware and software, IT management, finance and accounting services, etc.)

Management processes - establish regulations, requirements, methods, and systems for the operation of primary and support processes.

Adding detail

Although understanding the value chain is necessary if you want to have an accurate understanding of your organizational processes, it is, in and of itself, not enough. You must disaggregate downward in more detail and identify lower-level processes, just as work within the organization expands downward as value is created.

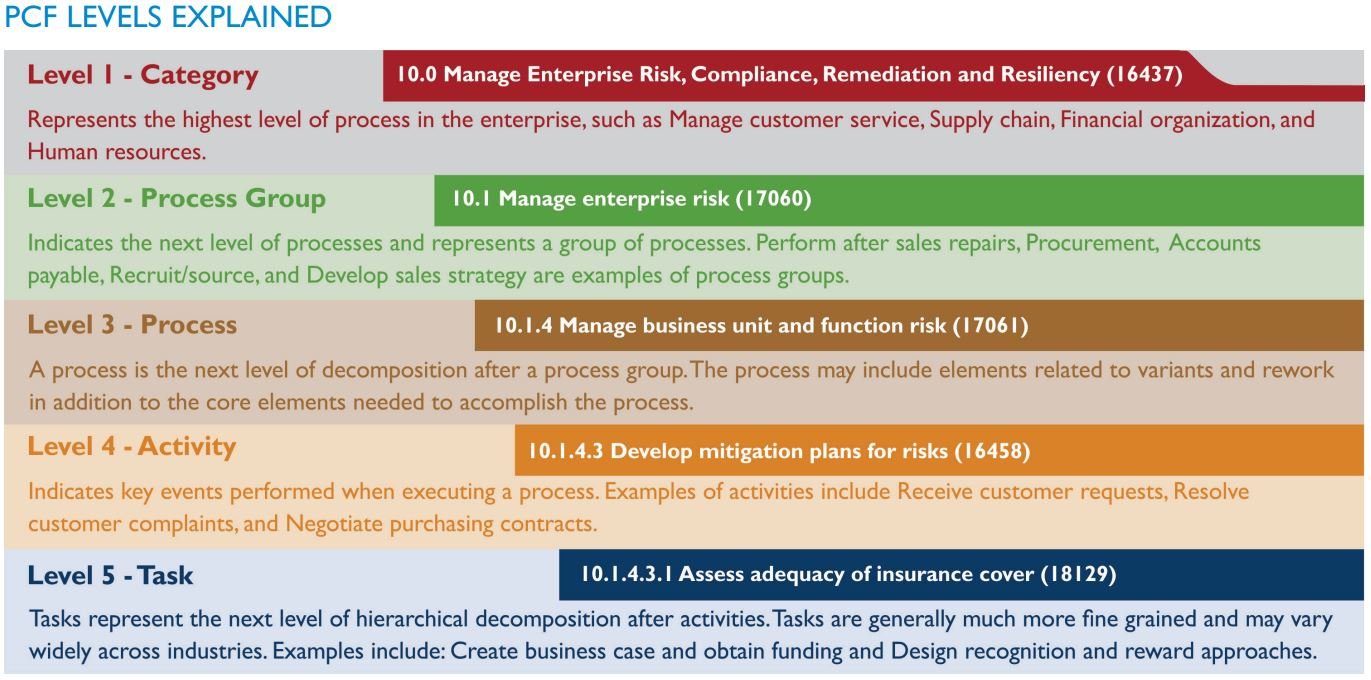

As I have explained before, the APQC PCF is a helpful resource for both understanding the levels of process detail and as a starting point for creating a process framework for your own organization. We have already established above that the PCF separates high-level processes into two classifications – operating processes (again, these are equivalent to Porter’s “primary” processes) and management and support processes.

Furthermore, the PCF also provides a model for process information as it breaks down into more granular levels of detail. Level 1 processes – where the operating and management and support processes live – are referred to as categories. There are 13 categories given in the PCF that can be seen in the image above.

As to how information in the PCF breaks down into more detail: Each category contains Level 2 process groups. Each process group contains Level 3 processes, and each process contains Level 4 activities and Level 5 tasks. So, we can see disaggregation from Level 1 categories (the high level) down to level 5 tasks (the most granular).

Example using PCF groups and processes

I spent a good portion of my career in the commercial construction industry. So, let us create an example value chain for a construction company using APQC’s PCF as a starting point.

Now, it is important to note that you should not simply copy the PCF (or any other reusable process framework) word-for-word. To make best use of it, you will want to change the terminology, so it is familiar and relevant to your industry and organization. You will also find that not every category, process group, or process in the PCF is relevant to your business. At the same time, you will find that there are certain items – particularly in levels 2-5 – that are important for your organization but are not represented in the PCF. So, in short, the PCF is simply a starting point for the development of an organization-specific process framework.

Construction value chain example - Level 1

As you can see in the above image, the operating processes – or value chain – for my construction company moves from “Develop Vision and Strategy” through to “Manage Construction Warranties.” I also referenced categories 7-13 from the PCF to help identify the appropriate management and support processes shown in the bottom row.

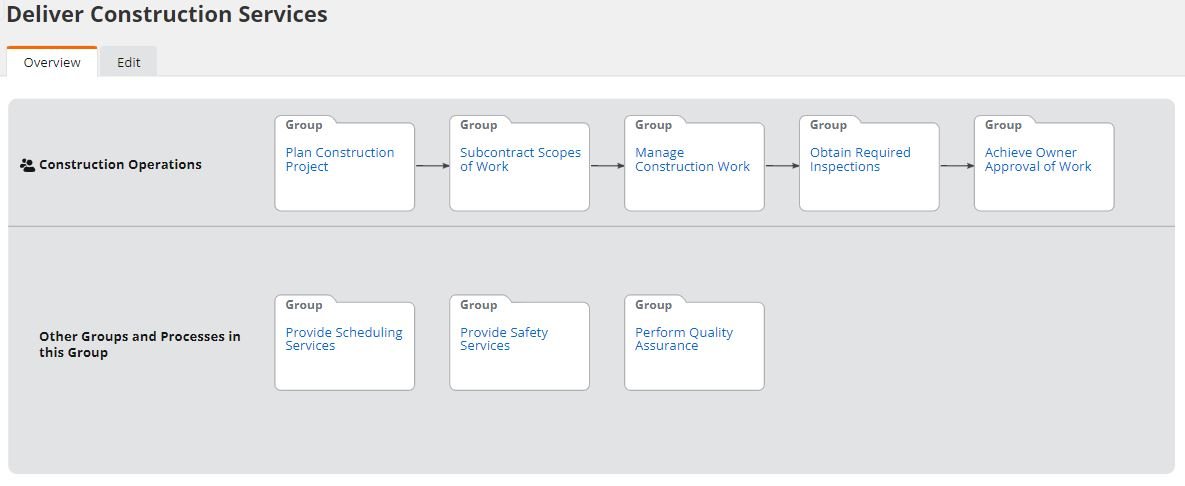

Next, we will disaggregate “Deliver Construction Services” downward into more detailed Level 2 process groups.

Deliver Construction Services process category example - Level 1 down to Level 2

The Level 1 category of “Deliver Construction Services” has five Level 2 operating processes and three Level 2 management and support processes.

We will drill down one more level by expanding the Level 2 process group entitled “Subcontract Scopes of Work.” In this process group, we will see the Level 3 processes that work in sequence to achieve the goal of subcontracting specific project scopes of work to appropriate trade partners.

Subcontract Scopes of Work process group example - Level 2 to Level 3

What we have modeled in this exercise is the disaggregation of process information from the highest level of detail – Level 1 categories – down to Level 2 process groups, and Level 3 processes using the example of a commercial construction company and the APQC PCF as our starting template.

Creating your own process framework

Although a process framework has five levels, not all five levels can or should be created at the same time. It is best practice to perform some measure of prioritization after categories, groups, and processes (Levels 1 – 3) have been identified before investing the resources required to understand, document, and improve process content at the activity and task level (Levels 4 and 5).

Just as building a house follows a logical progression – foundation, structure, sheathing, roofing, mechanical, interior finishes, etc. – creating a process framework follows a similar logical progression. You start high-level and work downward.

I recommend building Levels 1 through 3 (categories, groups, and processes) into your framework first. Then perform a prioritization exercise – perhaps using a tool like a decision matrix – to identify the best place to continue building downward into Levels 4 and 5 (activities and tasks) and focusing on process improvement.

Now what?

It is very easy to become overwhelmed with the prospect of identifying and organizing process information. My hope is that the information in this blog will make that effort less overwhelming. Remember, start by focusing on the value your organization produces.

In the simplest of terms, most companies are making stuff, selling stuff, and enabling the making and selling of stuff. Making and selling stuff is primary. Enabling the making and selling of stuff falls into the support and management categories.

Once you have identified the major processes for the three categories (primary, support, and management), you can define their horizontal relationship to create a value chain. Then begin working downward into each Level 1 process to establish the vertical relationships. Within your Level 1 processes there will be Level 2 process groups. Work downward from there – within each Level 2 process group, there will be Level 3 processes. So on and so forth.

Do not be afraid to use a reference such as the APQC PCF to help get you started. In fact, even experienced professionals can benefit from referencing such models. Draw from those in your organization who are experienced and know how work gets done. Above all, get started now and begin crafting your organizational process framework. It is one of the foundational components of a value-adding process management program.

[1] Michael E. Porter, Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance (The Free Press, New York, 1985), 36.

[2] Porter, Competitive Advantage, 38.

[3] Geary A. Rummler and Alan P. Brache, Improving Performance: How to Manage the White Space on the Organizational Chart (Jossey-Bass Publishers, San Francisco, 1995), 45.

[4] Marlon Dumas, Marcello La Rosa, Jan Mendling, and Hajo A. Reijers, Fundamentals of Business Process Management (Springer, Berlin, 2018), 41.

[5] APQC.org. https://www.apqc.org/system/files/resource-file/2022-05/K012570_PCF_Cross%20Industry_v7.3.0_April_2022_0.pdf (accessed June 16, 2022).